|

|

| |

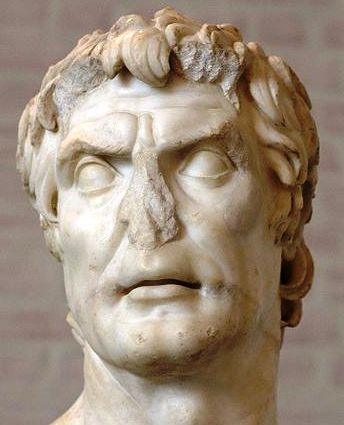

Sulla, Marble bust,

2nd c BC. Glyptothek Museum, Munich, Germany.

Sulla was a powerful and feared Roman leader. As "dictator," he tried to force

Julius Caesar to divorce his wife. He did not like her father's political

positions.

Highlights

*

Divorce

for most of Roman history was a private matter. It did not involve either

religion or the state.

*

Both the wife and the husband could initiate a divorce, either verbally or in

writing.

*

The wife's dowry had to be returned to her family upon divorce. It supplied the

resources for her remarriage. Any children remained with their father,

the husband.

*

Why Romans might divorce: high politics, the wife's failure to

produce children, or lust for a different mate.

* Under Emperor Augustus,

who ruled about the time of Jesus Christ, laws restricting personal

freedom became draconian.

|

|

Divorce in Ancient Rome

Divorce and remarriage in ancient

Rome--easily possible for most of Rome's history. A more advantageous second (or third or fourth) marriage on

the horizon? Out with the current spouse, in with the new one. Roman Politics and Divorce: Julius Caesar

Divorce often happened for political reasons. It might even be commanded. Sulla,

the fearsome Roman dictator of the 2nd century BC, ordered Caesar to

cast aside Cornelia,

Caesar's

first

wife. Why?--because Cornelia's father was Sulla's

bitter political opponent. But Caesar said no, and lived.

Caesar's survival took the intervention of his mother, Aurelia.

Sulla exacted his revenge. Spurned and angry, Sulla

seized Cornelia's dowry and other property. Caesar and his family became

impoverished.Roman Religion and Divorce

Religion could drive a divorce. Pompeia, Caesar's

second wife, was divorced for polluting a religious ritual. She

had an aristocratic lover, the odious Clodius. She snuck

him into a female-only religious ceremony presided over by the Vestal

Virgins. Into Caesar's own house as the Pontifex Maximus, no less.

And what

of Clodius? He was put on trial for sacrilege--and acquitted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Though marriage was honorable, it was not sacred. It was

not "holy" matrimony in the Christian sense.

In perfect alignment with Roman values, divorce

until the time of the Emperor Augustus was managed within the

family. Religious institutions or the state were not involved.

Divorce could simply be commanded by the head of the family of either husband

or wife.

To divorce, one party simply notified the other,

either verbally or in writing.

Divorce still had important

consequences. Marriage was a contract involving property and

expectations of inheritance, which divorce disrupted.

Under Emperor Augustus,

husbands elevated to the Senate had to have their wives' lineage

scrutinized. If the husband had married "beneath his class," he must

divorce and remarry. If a husband caught his wife in the act of

adultery, he not only had to divorce her, he had to prosecute her within

sixty days. If he did not, the husband could be prosecuted as well.

Divorced women were further penalized if they did not remarry within two

years. |

|

The downside of divorce

The husband

Upon divorce,

the husband forked

over the wife's original dowry per the marriage contract. Even if he had to

borrow money to do so. This allowed her family the means to

arrange her next marriage.

The wife

The wife had to return to her

father or guardian,

leaving behind any children from the marriage. In Roman society, the male had complete

power over and responsibility for his children.

For a Roman mother, was losing one's children a deterrent to

divorce? Perhaps, perhaps not.

The children

Children of divorced parents stayed with their father. Often there was

rivalry for property and power between them and any new children by

their father's next wife.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

You may contact me, Nancy Padgett, at

NJPadgett@gmail.com

|

|

|

|